Heritage

A Rough Beginning For Italians in America

From 1890 any Italians who were immigrants to the United States were considered part of what came to be known as “New Immigration,” which alludes to the third and biggest stream of immigration coming over from Europe and comprised Slavick peoples, Jews, and Italians. This was quite a change from the “Old Immigration” which comprised Irish, Germans, British peoples, and even Scandinavians and took place during the 19th century. It was also the start of Italian American history.

Between the years 1900 and 1915, an outpouring of 3 million Italians became immigrants to America, where they gained the dubious distinction of being the greatest nationality of “new immigrants.” Composed of almost entirely of peasants and artisans, they came from all areas of Italy, but most were from Southern Italy. The years 1876 to 1930 saw 5 million immigrants come to the United States. Out of these, 4/5 came from the southern portion of Italy, coming from areas such as Calabria, Abruzzi Campania, and Sicily. The greatest part of the immigrant population were laborers or farm laborers. The laborers did not have training in any industry such as textiles and mining. The small group of laborers who had worked in industry had left employment at textile factories located in Tuscany and Piedmont and mines located in Sicily and Umbria.

Along with the laborers, a small group of craftsmen traveled to the United States as well. They made up only a small part of all Italian immigrants and rated a higher ranking than the laborers. Most of the craftsmen were from the South and were able to read and write; among them were carpenters, masons, bricklayers, barbers, and tailors.

A record number of Italians immigrated to the United States in 1913. Most were from the northern part of Italy, but many still came from the South as well. Because of their great numbers, Italians soon became an essential part of organized labor in the United States. They made up a large part of the mining, clothing manufacturing, and textile industries. Actually, Italians had the greatest number of immigrants working in the nation’s mines.

Enduring Prejudice

Laborers and tradesmen both had to undergo ethnic and economic prejudices when they joined the American workforce. The economic antagonism arose from the role Italian immigrants played as “strikebreakers” from 1870 forward. What happened was that American workers were intimidated by the new machinery which was brought into various industries, and as a result, they held strikes in protest. The Italians eagerly stepped forward and took their jobs working as scabs. Southern Italians, in particular, were disliked for becoming scabs when there were strikes in mining, construction, the railroad, industry, and long shoring. Frequently, these southern Italians were called names and were made to labor beside blacks.

Employers tended to prefer Poles and Slovaks over Italians; railroad superintendents wouldn’t hire Southern Italians due to their short stature and because they weren’t strong enough for the tough manual labor required. Chiefly in mining, there was what’s known as an ethnic hierarchy. This meant that workers who spoke English were given the supervisory and skilled employment while the Italians were only employed as loaders, laborers, and pick miners. It took until the 1920s for Italians to become more of an accepted part of the American class. More Italian immigrants began to work semi-skilled and skilled jobs.

Reasons For Immigration

The chief reason why the Italians immigrated was poverty, but political reasons and the goal of returning to Italy with money enough to purchase land also spurred them on. For most Italians, farming was the way they made their living. It was hard, backbreaking work just by the nature of the work, but they also had to contend with farming tools that were outdated and lack of access to modern technology. All of this greatly limited their hopes for improving their lot in life. Frequently the farmers had to endure living in grim conditions, their homes one-room houses that lacked both privacy and plumbing.

Furthermore, many peasants remained isolated because Italy had few roads. They couldn’t leave their land to find jobs in the city and in most cases, even if they could, they wouldn’t have been able to afford to take the risk. Plus, the land was controlled by landlords who charged high amounts for rents, gave low pay, and were a source of unsteady employment. What made immigrating to America all the more appealing was the much higher pay American workers earned.

Adding to the already critical situation of Italian farmers, an agricultural crisis hit Italy in the 19th century and caused grain prices to drop and the demands for fruit and wine to almost disappear. What led to all this was a disease, phylloxera, which killed off the grapevines needed to make wine.

Considering all of this, the United States was viewed as a nation with plentiful land, reasonable wages, lower taxes, and another selling point, no military draft. Feeling that there was considerably more hope in America the Italians began to come in droves.

A lot of Italians weren’t giving up on their country. They wanted to buy land in Italy, so they moved to America temporarily to earn money, then repatriated to their homeland now able to be successful, something they could never have accomplished had they remained in their own country where conditions weren’t likely to change any time soon.

Another point in favor of immigration was political hardship. Beginning in the 1870s the Italian government determined to repress political beliefs. So many Italians also came to the United States hoping to escape political repression.

Although they have largely accomplished their goal of being accepted into American society, Italian Americans have managed to keep certain distinguishing characteristics. In the cities, they have remained concentrated in the old settlement areas, and they have retained their strong attachment to family loyalty, and their support for domestic values.

The history of Italian Americans and how they left their homeland to build a new life in the United States of America is a fascinating one. Considering how they were not easily assimilated into the American culture, and battled for their place in the workforce, it is not a story without its hardships, but the strong spirit of Italian Americans dominated their many adversities and they were able to overcome them and thrive in this country to this day.

-

Heritage4 years ago

Heritage4 years agoWhat it truly means to be Italian

-

Italian4 years ago

Italian4 years agoNew York vs Chicago Pizza

-

Heritage4 years ago

Heritage4 years agoItalians And Family Values

-

Italian4 years ago

Italian4 years agoTop 9 Popular Italian Pastries

-

Heritage4 years ago

Heritage4 years agoEllis Island Italian Americans

-

Italian4 years ago

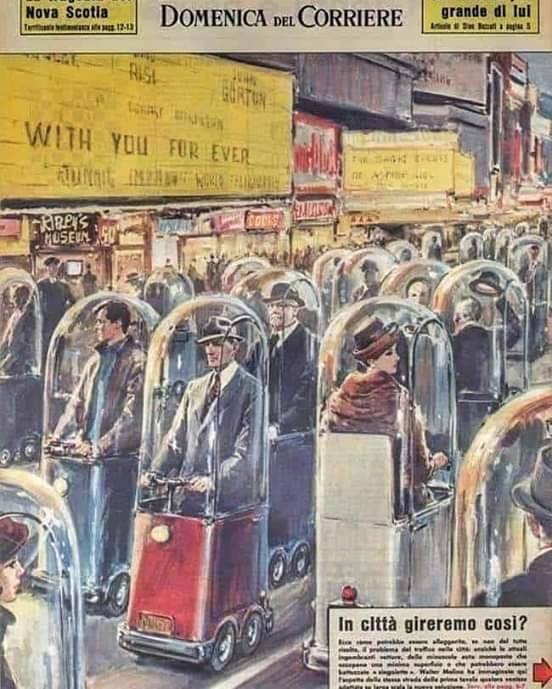

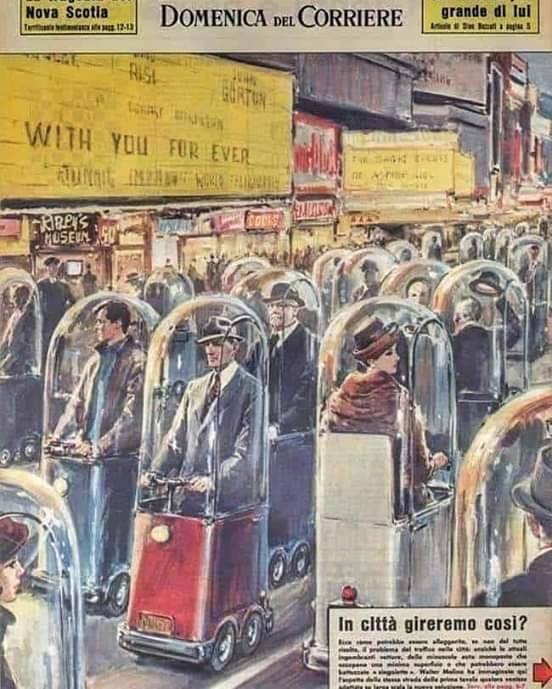

Italian4 years agoIn 1962, an Italian magazine carried a story on how the world will look in 2022. Is it Real???

-

Heritage4 years ago

Heritage4 years agoHow Italian American families celebrate holidays

-

Heritage4 years ago

Heritage4 years agoColumbus and the Legacy of Italian Americans

Ed St. Thomas Jr.

July 11, 2020 at 10:07 pm

I am a bit apprehensive about leaving a comment as I’m only 50% Italian. But here goes: My Dad and his family were from the town of Chiaromonte, Potenza in the Basilicata Region. The family name was originally Santomassimo. His older sister, Rose, was my favorite Aunt growing up. (What Italian family doesn’t have an Aunt Rose?) What I remember most growing up were the all day feasts at his sister Linda’s on Easter and Thanksgiving. So much food! My Aunt Linda’s family nickname was Mammy Yokum because of her earthiness. I was about 9 years old and was visiting with her and helping her work in her large garden. When I told her I had to go to the bathroom, she asked me: “Number 1 or number 2?” After I said “Number 1,” she told me, “Go over there behind that bush.” Like I said, very earthy. My Grandfather, Francesco Santomassimo, was the Vice Consul at the Italian Embassy in Newark, NJ from 1915 until 1927.