Heritage

Ellis Island Italian Americans

There is no place in the United States that is filled with quite as much history as Ellis Island. Over twelve million immigrants entered the United States through the iconic port of entry nestled in New York Harbor. Chances are, someone in your family’s history probably came through there, too. It’s estimated that 40% of Americans can trace their family’s immigration story through the records of Ellis Island. If your family has Italian heritage, it extremely likely that they too entered the country through this now world famous island.

The Italian Migration

During the height of American immigration in the early 1900s, over two million Italians made their way to New York Harbor and passed through the halls of Ellis Island’s buildings, entering their new nation for the first time as citizens. By the time the great immigration boom ended in the 1920’s, more than four million Italians had passed through Ellis Island. At this point in history Italians accounted for more than 10 percent of the United States’ immigrant population.

It is believed that a majority of southern Italians who emigrated during this time due to the tense situation happening in the region at the time. At the time, Italy was made up of separate city states and kingdoms. Southern Italy was known as the Independent and Sovereign State of southern Italy, also called the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. In 1860 the kingdom was suddenly occupied by the northern Piedmontese Kingdom. The invasion resulted in a 10 year civil war that left the south battered and economically broken. The economic hardship and threats of violence were a huge motivating factor for many Italian emigrants.

Birds of Passage

Very few Italian immigrants intended to stay in the United States forever. This was proven by the fact that a majority of them did not go into farming, a very common profession in their hometowns. They chose instead to work in higher wage labor jobs, using the higher wages to send money back home to the families they left behind in Italy. Many men left their wives and children behind, intending to come home again (which many did).

Italian immigrants were given the nickname “Birds of Passage” for this very reason. Their intention to be temporary residents and migrant workers. While many Italian immigrants did eventually make their way home to a safer, more stable Italy, there were many whose ticket remained one-way, oftentimes resulting in their families and neighbors making their way to the United States by means of their financial support.

Entering Ellis Island

Like all immigrants to the country at the time, all of these hopeful Italian Americans were forced to endure long journeys and grueling review before they were officially admitted to the country. The records at Ellis Island document for us very clearly the process required and the incredible speed at which immigrants were admitted into the country, a stark comparison to the modern immigration process we see today.

Before any ship was able to enter New York Harbor it was required to enter a checkpoint on the Staten Island coast. Ships were placed in a temporary quarantine, with doctors boarding the boat to check for common infectious diseases at the time such as smallpox, cholera, or yellow fever. If the ship was able to pass the doctor’s inspection, they were able to move on to the next step in the immigration process.

Ship passengers were dismissed in order of their class on the boat. First and second class passengers were dismissed first and allowed to leave the boat immediately upon docking. There were no passports or paperwork required, only a verbal confirmation upon your departure from Europe. The steerage passengers were not quite as lucky. They were often stuck in the quarantined boat for hours (or even days) before they were given clearance to disembark.

Steerage passengers were given manifest tags so their information could be easily identified by immigration inspectors and customs officers upon entering the country. Their baggage was checked, too. Upon approval of the customs agents, they were then placed on steamboats headed for Ellis Island. These steamboats would deliver as many as 10,000 passengers to Ellis Island each day.

Upon entering Ellis Island, passengers were subjected to medical inspections, having been divided into lines for men and women and children prior to leaving the steamboat. They were quickly inspected for visible diseases and disorders, as well as general health. Those who did not pass were moved to a doctor’s pen (a glorified cage) for further examination, although this was not common.

After the medical examination, immigrants were brought to the immigration inspection. This was to verify passenger information. If your answers weren’t deemed suspicious, you were welcomed to the United States with little to no fanfare. No passport check. No documents to sign. No citizenship test. You simply walked out the door an American. The entire process from ship departure to final inspection took around 3-5 hours.

It Took A Village

Unlike many of the immigrants who had passed through Ellis Island before them, Italian Americans stuck around New York City. One third of the Italian immigrants that came through ended up making NYC their permanent home. All of the boroughs became home to these newly minted Italian Americans, but a vast majority of them stayed in the area of Manhattan.

Much like the divisions that occurred in their home countries, the new communities that popped up in New York City were drawn based on the regions they called home in Italy. Southern Italians stuck with Southern Italians, while those immigrants from the North created their own communities. It wasn’t uncommon for entire villages from Italy to end up in the same small neighborhood in the United States.

These neighborhoods became the cultural heart for Italian Americans. Life milestones such as weddings, funerals, and baptisms were large scale events. These mini-Italian villages also hosted their own parades and religious celebrations, often commemorating the patron saint of their native Italian village. They were an embedded support system and a balm against the sting of homesickness.

-

Heritage4 years ago

Heritage4 years agoA Rough Beginning For Italians in America

-

Heritage4 years ago

Heritage4 years agoWhat it truly means to be Italian

-

Italian4 years ago

Italian4 years agoNew York vs Chicago Pizza

-

Heritage4 years ago

Heritage4 years agoItalians And Family Values

-

Italian4 years ago

Italian4 years agoTop 9 Popular Italian Pastries

-

Italian4 years ago

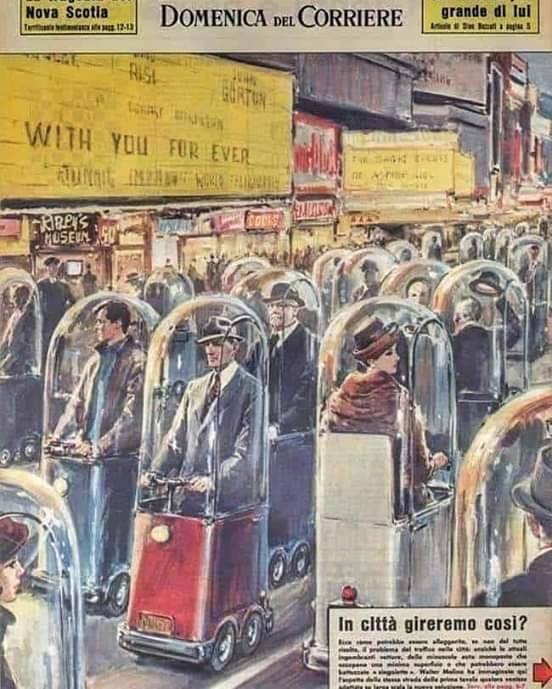

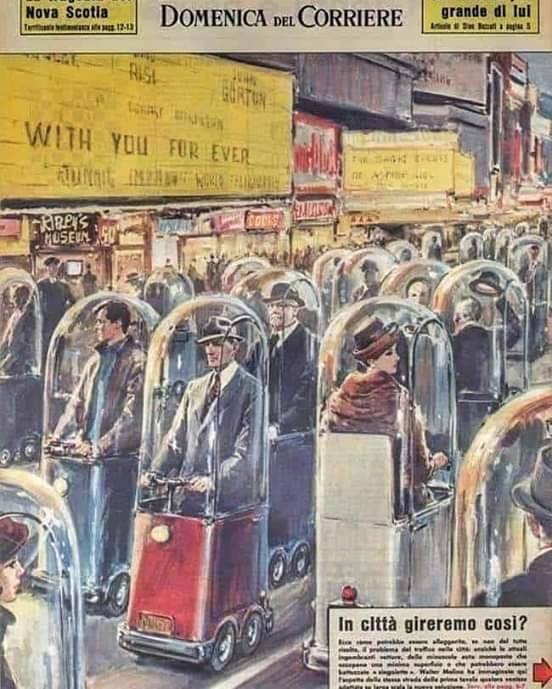

Italian4 years agoIn 1962, an Italian magazine carried a story on how the world will look in 2022. Is it Real???

-

Heritage4 years ago

Heritage4 years agoHow Italian American families celebrate holidays

-

Heritage4 years ago

Heritage4 years agoColumbus and the Legacy of Italian Americans